by M. Kathy Raines

I ran screaming from the gentle surf one Sunday morning decades ago, fearing a shark had shorn off some flesh.

Then, tormented by what seemed like a thousand bee stings, I peeled off several purplish tendrils pasted to my blistered thighs. I never saw the Portuguese man-of-war’s balloon. But tentacles from even a dead creature pack a powerful sting.

Beach people rushed over, dispensing advice, including to coat it with meat tenderizer, which I did. The agony subsided shortly, and I was fine.

A Portuguese Man-of-War (Physalia physalis), also dubbed “bluebottle,” is not a jellyfish. Rather, it is a siphonophore, a colony of same-sexed organisms, called polyps or zooids, working cooperatively as one. This creature has four of them.

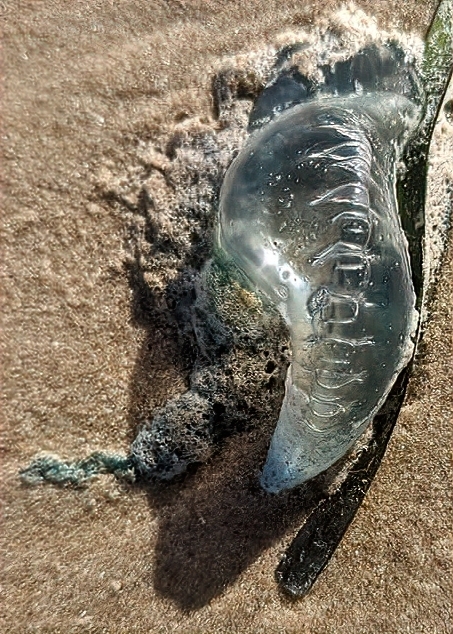

Its lacily helmeted, dimpled pneumatophore—a translucent, gas-filled balloon of sunset pastels—bobs in the surf, buffeted by winds and waves, with no volition of its own. However, when threatened, it can use its siphon to slightly deflate and briefly submerge.

Portuguese men-of-war, steered by the same winds and waves, may wash up on beaches en masse. If alive, the pneumatophore, accompanied by a gooey gnarl of purplish tentacles, may appear to gently nod. The creature’s name may originate from its upper membrane’s resemblance to a Portuguese warship at full sail or to the warriors’ helmets.

Secondly, its tentacles, or dactylozooids—armed with venom-delivering nematocysts— paralyze ill-fated fish, crustaceans and others swimming among the tendrils. Tentacles, usually about 30 feet long, can reach 165 feet.

The tentacles deliver prey to the third group, the gastrozooids, or digestive polyps, each with a mouth, from which it excretes indigestible matter.

The Portuguese-Man-of-War’s fourth polyps are the gonozooids, those responsible for reproduction. The creature reproduces sexually via broadcast spawning, during which large groups assemble and both males and females release eggs and sperm simultaneously. The resultant larvae reproduce asexually, through budding, finally forming a mature colony.

This collective creature’s four zooids communicate through a network of nerve fibers.

Loggerhead turtles feed on Portuguese-men-of-war, and the man-of-war fish or shepherd fish, partially immune to its venom, nibbles on and lives among their tentacles. The blanket octopus, also immune, yanks off tentacles to use for its own defense. The blue sea slug, likewise immune, feeds on the creature, storing its stinging nematocysts for use against potential predators.

First aid advice for treating stings from Portuguese Men-of-War varies, even among reputable sources like the Red Cross. And, apparently, we should throw a container of vinegar in among our beach towels. A 2017 study written by scholars from the University of Houston and published in the journal Toxins recommends the following: 1. Douse the skin with vinegar, rinsing off tentacles and deactivating stingers. 2. Pluck out tentacles with tweezers, not sand or a credit card, which could spread or trigger stingers. 3. Apply heat, via warm water or a hot pack for about 45 minutes.

Sting No More, a commercial product developed for military divers, also eases pain. A 2012 study found large amounts various brands of meat tenderizer to be somewhat effective.

Fatalities are rare, but severe symptoms like nausea, muscle pain, headache, chills, dizziness or breathlessness require immediate medical attention.

Ineffective remedies include alcohol, urine, baking soda, lemon juice, dish soap and sea water, the latter of which may worsen the spread.