by M. Kathy Raines

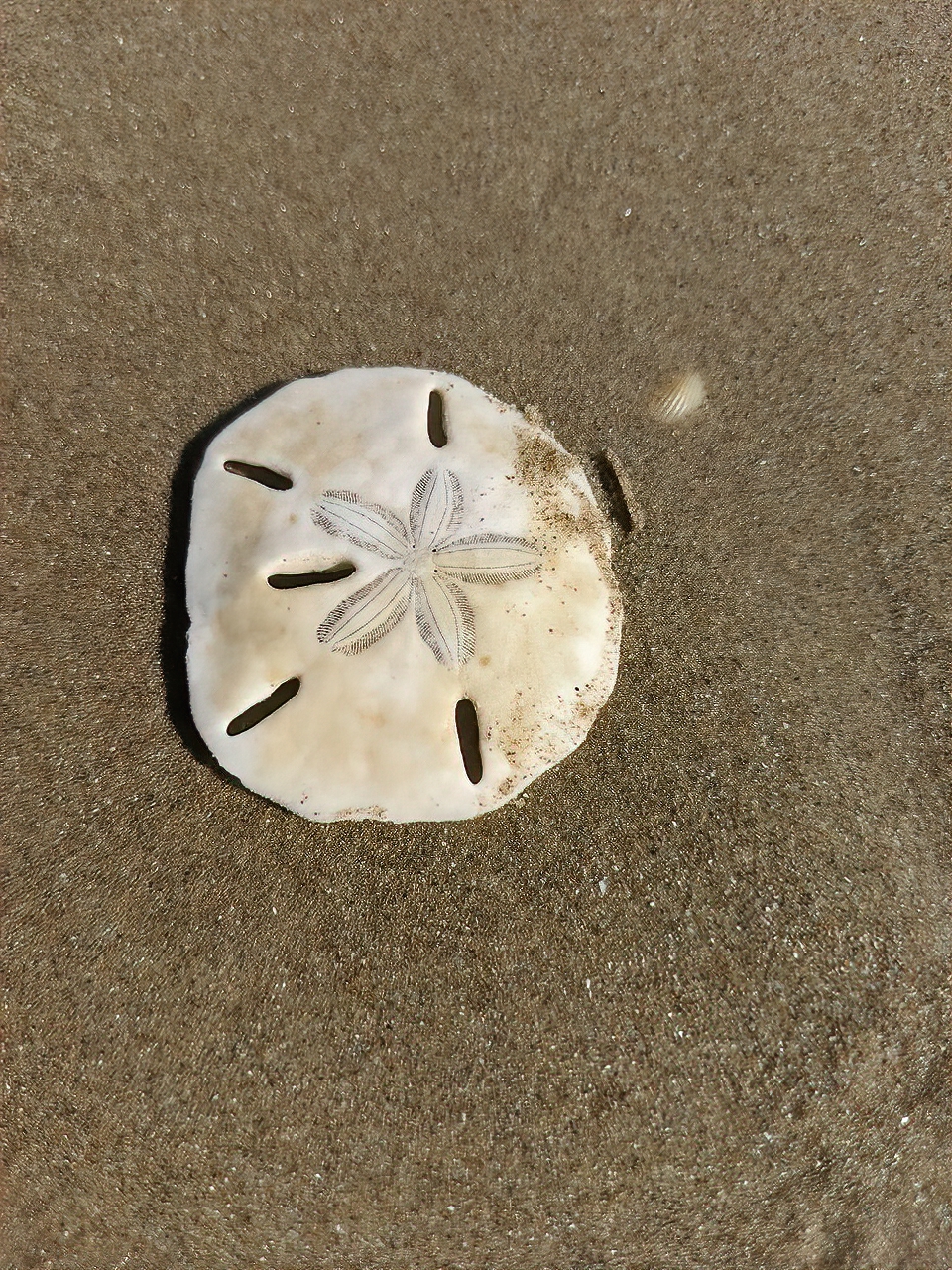

“I found a sand dollar!” we cry, picking up the enchanting little wafer, its dainty, symmetrical five-petaled flower and five perforations evoking joy and calm.

Yet, what we thrill to see along the shore is merely the sand dollar’s sun-bleached test, or endoskeleton made of calcium carbonate. If we waded further, or snorkeled, we might see its live companions along the second or third sandbar in their brownish or greenish grandeur, their velvety tube feet and cilia-coated spines busily feeding on tiny aquatic life.

Our local sand dollar is the keyhole urchin (Mellita quinquiesperforata), which Spanish-speakers sometimes call galeta de mar (sea cookie) or dólar de arena (sand dollar). It thrives in the Gulf and Caribbean as well as warm, salty bays and Atlantic waters from Virginia to Brazil. This spiny-skinned creature is an echinoderm, like a starfish and sea urchin, with whom it shares its five-point design. In fact, it is so like an urchin—which hides in and clings to rocks rather than sandy bottoms— that some call it a flat sea urchin.

Lunules, five rows of oval, petal-like pores, dot the sand dollar’s surface. Though their purpose is unknown, research suggests they may help anchor the creature, as well as assist with absorption of water and food. Its petaloids, or decorative “petals”, consist of miniscule holes through which the top podia, or tube feet, emerge. It employs these for respiration and sifting food from sand. Its centrally located mouth, a hole clearly visible in its skeleton, and its anus are on the bottom.

When partially buried and slanted vertically, as it is in calm waters, a sand dollar snags prey with its cilia-covered spines and feet. In rougher surf, it lies flat and, if confronted by a predator, buries itself. Like a velvety conveyer belt, cilia-covered spines intermixed with more podia and mucous, transport captured food particles along its body and into its mouth. This, dubbed Aristotle’s Lantern, for its resemblance to the ancient Greek five-sided lantern made of fragments of horn, has five teethlike parts that pulverize microscopic algae and animal fragments. It may chew for a quarter hour and digest for two days.

A dried test contains detached, dove-shaped “teeth” which may rattle and fall out when broken. Dubbed “doves of peace”, they have even inspired an anonymous poem, “Legend of the Sand Dollar”: “Now break the centre open/And here you will release/The five white doves awaiting/To spread Good Will and Peace.”

Since sand dollars broadcast their sperm and eggs into the water to be fertilized, hundreds of sand dollars amass together. The ova, fertilized in late spring to early summer, develop into planktonic larvae, which drift for four to six weeks, feeding and undergoing several transformations. For instance, larvae gradually sprout an increasing number of arms, eventually numbering eight, before, at about six weeks, they grow tests and settle onto the seabed.

Larvae, when threatened by certain predators, may clone themselves, presumably to become tiny enough to escape. Researchers at the University of Washington discovered this when they exposed four-day-old larvae to water containing mucous from the Dover sole, a common predator. Within 24 hours, these larvae, unlike those which had not been exposed, had split into two smaller but identical creatures. This cloning response is presumably predator-specific, as tinier larvae may become more vulnerable to miniscule foes like planktonic crustaceans.

Young sand dollars consume sand grains, including—as demonstrated by X-rays and magnets—those containing magnetite, or iron ore, to weight them down, especially in roiling waters.

A sand dollar—as determined by the number of growth rings on its test—can survive about ten years. One formidable predator is the scotch bonnet, an orange and cream sea snail which bores holes through its test, rasping out edible parts. Other threats include assorted fish, crabs, starfish and nurse sharks.

Human threats include bottom trawling, ocean acidification—which inhibits test production—and reduced salinity, as the creatures prefer salinity more than 2.3 parts per thousand. It is wrong, and illegal in some areas, to collect a live sand dollar—recognizable by its spines, which are shed shortly after death. Also, a live creature emits echinochrome, a substance that dyes one’s fingers yellow.

The following YouTube video, though it concerns the Pacific, or eccentric, sand dollar (Dendraster excentricus), excellently portrays the live creature’s appearance, feeding and other habits: https://www.pbs.org/video/a-sand-dollars-breakfast-is-totally-metal-x1r1zt/.