This past week saw 1,165 Texas Master Naturalists from all 48 chapters across Texas attending the annual conference — virtually.

One particular technical session resonated with me because it allowed me to finally be a guilt-free gardener! Yes, I have a guilty secret. I harbor some non-native plants in my gardens. And that’s ok!

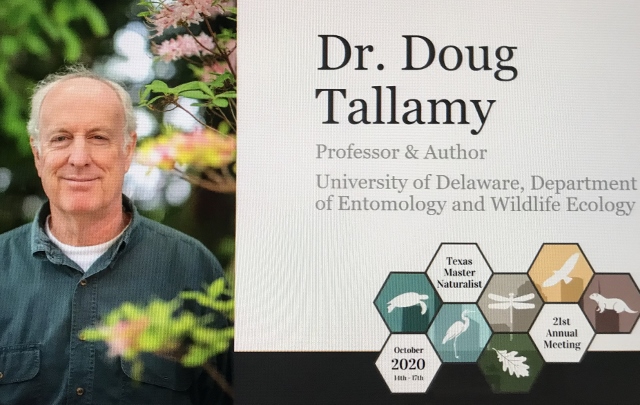

Doug Tallamy, PhD, professor at the University of Delaware’s Department of Entomology and Wildlife Ecology, and author of a recent book, “Nature’s Best Hope — Restoring Nature’s Relationships,” gave an outstanding presentation with workable ideas whereby he proposes that we can make our “combined yards” — across the nation — “into the largest nature park” in the United States and offer “Nature’s Best Hope” to heal the land and recover from decades of landscape abuse.

Tallamy’s concept is to promote ideal habitats for caterpillars.

Here’s how it can work: By shrinking lawn areas at every residential yard across the nation, and replacing that portion with designed, layered landscapes using primarily native plants — and just as importantly — incorporating local ornamental plants at a less than 30 percent proportion of the designated planted area, habitat can be established that will promote and sustain butterfly and moth caterpillars.

Yes, many caterpillars are host plant specific, and other caterpillars are plant family specific. Research for host plant information is called for prior to planting.

Why caterpillars? Tallamy purports that it is the species that contributes the most to ecosystem function. He advocates that we need to renew all parts of nature, but for now, focus on caterpillars because in terms of sustaining food webs, caterpillars are essential.

For instance, 90 per cent of birds feed their young on caterpillars. When insects decline, birds decline. Another reason to encourage caterpillars is that they transfer more energy from plants to other animals than any other plant-eaters. We can add caterpillars to landscapes by adding the plants that support them.

Tallamy’s concept isn’t just good for Delaware, it’s a viable idea for anywhere in the world, using plants native to any given geographical area and ornamental plants that are also area specific and ecologically productive — in other words, cultivated plants that would not become destructive to the environment.

In Delaware, Tallamy offers a statistic that just five percent of their native plants make 75 percent of the caterpillar food that drives food webs. That statistic, or close to those same numbers, is imaginably similar in ecoregions anywhere.

From my yard, in the past three years, I’ve identified — via iNaturalsit.org — 253 Lepidoptera family insects — 189 moth species and 64 butterfly species.

- Worldwide, there is thought to be about 160,000 species of moths and 17,500 species of butterflies — respectively, 11,000 and 750 in the United States

- Each species of moth lays a different number of eggs, and the range is vast: Some lay as few as 40 at a time, some up to 1,000.

- Depending on the species, female butterflies lay eggs one at a time, in clusters, or in batches of hundreds. Butterflies lay an average of between 100 to 300 eggs; although some species may only lay a few dozen, others can lay as many as a thousand or more. — Statistics courtesy of Wikipedia

That’s a lot of potential caterpillars — a lot of nourishment up the food chain to sustain the diversity I enjoy in my yard, such as lizards, birds, snakes, armadillos, bats and other critters.

I’d like to expound on Tallamy’s concept of successfully incorporating non-native plants to provide viable caterpillar habitat with an example of what I experienced this week in a small section of our land: the courtyard.

This past month I have set up my moth-attracting apparatus at the courtyard wall, at the end furthest from the front porch. It’s been a varied and interesting time attracting the moth population of late summer and early fall.

The most fun was about four days ago when a new moth showed up — a satin white palpita (Palpita flegia).

Then the next morning a couple of hours before the sun came up, I ventured out the front door. The ceiling of the porch was speckled with half a dozen satin white palpita. The shrub closest to the porch — don’t gasp — is a non-native, a six-year old pride of Barbados (Caesalpinia pulcherrima), also called Poinciana bush. It is in full bloom. Another half dozen satin white palpitas were resting on its leaf clusters.

Across the sidewalk from the pride of Barbados is a huge night blooming jasmine (Cestrum nocturnum), also in full bloom.

The night blooming jasmine was a sparkling fairy land of luminous white fluttering wings from dozens of satin white palpita, each drawing nectar from as many blooms as possible in an erratic ballet of flight around and into the depths of the shrub. It was magical.

The moth sheet held another half dozen satin white palpita.

Other than for my entertainment value, there are other reasons to allow a few non-native species in a garden, always using prudence and safe landscape practices.

During late summer, the pride of Barbados is one of the busiest plants in my yard with more than a dozen different species of butterflies attracted to its vibrant orange and yellow blooms. Hummingbirds, bees and humingbird moths also draw nectar from the blooms.

We planted the night jasmine shrub because of its beautiful scent and also in an attempt to attract night pollinators, possibly nectar bats and the large and colorful sphinx moths.

Another non-native shrub, planted just over the courtyard wall, is a Confederate rose, Hibiscus mutablilis. In addition to providing nectar to butterflies and bees, it is one of 26 native and non-native plants in our yard that is used as larval food for the giant leopard moth caterpillars and others of the tiger moth tribe. For more about the Confederate rose, check out this link: https://rgvctmn.org/a-rose-is-a-rose-unless-its-a-hibiscus/

All three of these particular non-native plants are nectar rich and just as importantly, they provide nectar during different seasons. The pride of Barbados blooms late spring through November, Confederate rose begins blooming in October and through the winter while night blooming jasmine blooms several times from spring to winter. Confederate rose keeps its leaves all year, providing larval food option for certain caterpillars.

Of course discretion is paramount. For Valley residents, check this website to ensure nothing is planted that is listed as a Texas invasive species: https://www.texasinvasives.org/plant_database/index.php

Leave a Reply