More fun with words. Fasciation is a weird word for a weird botanical condition. Computer auto-spell likes to change the word to fascination, and, I must admit, I found the subject rather fascinating.

Fasciated (pronounced: făsh′ē-ā′tĭd) is defined as:

“Compressed into a bundle or band; grown closely together, with the stems malformed and flattened as if several separate stems had been fused together.”

Reference — Harris, J. G. and Harris, M. W. 2015. Plant Identification Terminology: An Illustrated Glossary. Second Edition. Spring Lake Publishing, Spring Lake, Utah. — ISBN 0-9640221-76-8

The Indian blanket flower on the right in the above photo is fasciated.

The simple explanation is, it’s an anomaly.

For those who enjoy a more definitive explanation:

It is a rare, abnormal growth in vascular plants (plants that possess conductive tissue — xylem* and phloem**) in which the growing tip (commonly the flowering part) which is normally concentrated around a single point and producing approximately cylindrical tissue, instead becomes elongated perpendicularly, producing a flattened, ribbon-like, crested, or elaborately contorted, tissue.

* Xylem — the water conducting tissue of vascular plants.

** Phloem — the food conducting tissue of vascular plants; bark.

Photographers often acquire a habit of noticing anomalies. The above fasciated Southern Indian blanket, Gaillardia pulchella, flower jumped out at me while strolling along Ramsey Park’s Ebony Loop near Coral Bean Cove with plant guru, Frank Wiseman. Frank had a ready explanation. “That’s fasciated,” he said. “What?” I asked, thinking he was slurring his words. I had him spell it while I tapped it in my “note” phone app to look up later.

Frank captured a Texas mountain laurel with a fasciated flower growth near the Arroyo in Harlingen’s Hugh Ramsey Nature Park.

Texas mountain laurel, Sohpora secundiflora, is in the fabaceae (pea) family and normally the flowers would be clusters of fragrant, purple, pea-like flowers, like those depicted below in a photo from the Lady Bird Johnson Flower Center’s Website, www.wildflower.org

According to one Website, fasciation has several possible causes, including hormonal, genetic, bacterial, fungal, viral and environmental. Read more about causes at:

https://www.uaex.edu/yard-garden/resource-library/plant-week/fasciated-2-22-08.aspx

One of my favorite spring-blooming native plants is Argemone sanguinea, white-blooming red poppy, often called prickly poppy.

Frank happened upon a fasciated native poppy.

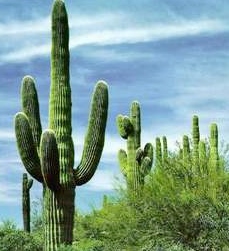

Perhaps a more iconic example of fasciated, or crested, growth is Arizona’s saguaro cactus, Camegiea gigantea, as shown below.

A fasciated phenomenon doesn’t just occur in flower heads. Roots, stems and fruit can be fasciated.

Plants rely on a growing point, called the apical meristem, *** to produce new parts and pieces.

*** Meristem. Undifferentiated, actively dividing tissues at the growing tips of shoots and roots.

Meristematic cells eventually transform themselves into leaves, stems and flowers. These meristem cells are biologically pliable, somewhat like human stem cells; occasionally things go amiss and fasciation happens.

Fasciation is especially common in cacti and succulents. Willows, cockscomb and foxgloves also frequently show this abnormality.

I was amazed to learn that one of my all-time favorite plants, cockscomb (Celosia), was especially prone to fasciation.

When I lived in Kansas, I acquired seeds from a stand of cockscomb that had re-seeded itself in an active cow pasture for more than fifty years. I successfully grew more than twenty plants from those seeds. Most of them had beautiful, velvety flower heads the size of a dinner plate. The plants grew to four and five feet in height. These cockscomb were so gorgeous, I would gaze into their depths and absolutely marvel at their stunning and intricate design.

In the fall, monarch butterflies covered the flower heads. It was thrilling.

Now, researching for this blog, I discovered that cockscombs really should look like the photo on the seed packets you find in revolving stands in the garden area at retail stores:

Apparently, the huge, swirly ones I grew are considered fasciated.

While fasciation in flowers is usually a one-time occurrence, sometimes the fasciation is carried in the plant’s genetic material so that it reoccurs from generation to generation which apparently was the case with the cow pasture cockscomb.

More often, fasciated plants have to be propagated vegetatively to carry on the unusual characteristics. Some horticulturalists intentionally try to reproduce fasciated plants by using grafting or cutting propagation methods, proving the old adage that beauty is in the eye of the beholder.

On your next nature outing, or in your own garden, perhaps you’ll see some of these genetic quirks and start a photo collection of your fasciated discoveries. Let us know what you find!

Leave a Reply