by M. Kathy Raines

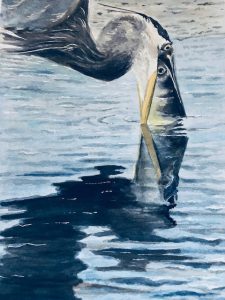

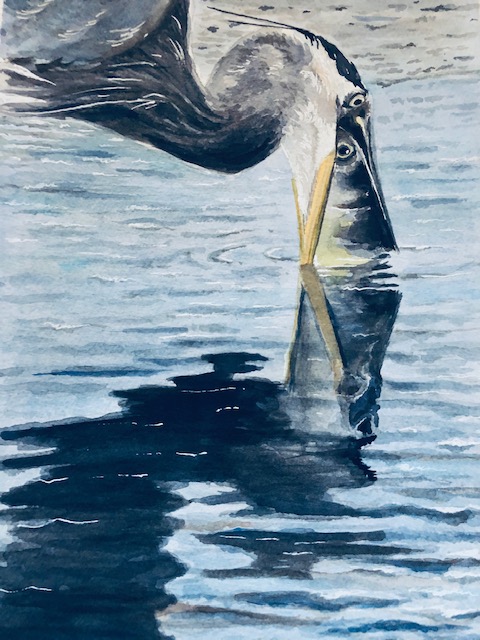

We missed the stabbing. But we witnessed the aftermath.

Gripping the mullet head to gullet—eyeball-to-eyeball—the heron dunked it in the water, lifted it, shook it, paused and repeated. Then it toted the fish into nearby thegrasses, dropped it, gazed about, picked it up, then did it again. Then it doused it in water. This process, whose purpose mystified me, continued.

Twenty minutes into this heron’s endeavors at the South Padre Island Birding, Nature Center & Alligator Sanctuary, my sister and I, being driven not by a predator’s keen hunger, but by curiosity, lost patience and departed, mystery unsolved.

Did the heron persist? What was its strategy? I have witnessed a heron adroitly maneuver a fish headfirst, fins folding reliably, so it slides down its gullet. Did this repeated lubrication ease the fish’s passage? A heron may give a fish a good shake to loosen its spines. Great Blue Herons, have, on occasion, choked on over-large prey.

The Great Blue Heron (Ardea herodias), a formidable predator with a flexible diet, breeds throughout Texas—nests have even been recorded in the arid Trans-Pecos region—and lives at least part of the year in every state in the U.S. Though those east of the Mississippi tend to migrate, many herons hunt mice and voles in the snow and shiver along frozen streams. Encountering one on a river boulder in Indiana one chilly October day, I thought, Dear heron, what are you doing here in the chill? These birds appear year-round in Montana and have even built winter nests there.

Though primarily found near seashores, tidal flats, lakes, rivers and creeks, Great Blue Herons also thrive in flooded fields, ditches, and pastures. An opportunistic feeder, this heron eats turtles, frogs, snakes, baby alligators, and various rodents. One YouTube video, shows a heron stalking, carefully manipulating, gulping down, then upchucking a sizeable gopher. Then the heron, spying a swooping red-tailed hawk, abruptly flutters away, sacrificing the doomed rodent just as the hawk swoops down and snatches it.

A Great Blue Heron typically stands and wades slowly and soundlessly, with nary a splash, its elongated toes and feet anchoring it on muddy bottoms. Being four feet tall, it can wade to its belly as it silently draws each leg up like a mop, then replaces it. Then, its ‘S-shaped neck providing momentum, it lunges forward and, with lightning speed, thrusts its sabre-like bill through its prey.

This heron may also dive feet-first for prey, hover and glean its food, or dine while swimming. It may also catch fish while floating or while sitting atop, say, a drifting wad of kelp. On beaches, the birds tend to forage during low or ebbing tides. The heron simply picks up small prey in its mandibles. Great Blue Heron –photo by Andrew Dressel (Public domain)

A Great Blue Heron has reportedly fished with bait, employing breadcrumbs tossed to geese. These herons, which primarily use eyesight for their endeavors, forage both daytime and evenings, the numerous rods in their eyes enabling them to see well at night.

In Texas, these herons breed mainly from late January through late August, a period during which their irises redden, legs turn pinkish orange, and plumes blossom from their backs and lower necks.

Varied and elaborate displays inaugurate breeding—ones that include extending the neck, raising the bill almost vertically, exposing and exhibiting certain elaborate plumage, fluffing the neck, and “bill clappering,” or a fast clicking of bill tips toward a mate. In the “greeting ceremony,” a bird joins its mate on the nest, giving a call, while the other stretches with an arched or fluffed neck display. In the “stick transfer ceremony,” the male offers his mate sticks for the nest, and, doing a stretch display, she receives the gift; he then clappers while she weaves them into the nest.

Colonial nesters, these herons construct stick nests high in shrubs or trees or even on the ground in sites with few predators. They also nest on isolated islands. The male selects the site and gathers most substances while the female does construction. Both incubate the eggs, the male sitting more often during the day, the female, at night. Their three to six large blue eggs hatch in 28 days, with birds fledging at two months. Training to become master predators like their parents, young birds play at stabbing inanimate objects.

This heron flies with its neck in an ‘S’ with legs trailing behind, and it walks erect with long strides. It may roost solitarily or in loose flocks of perhaps a hundred.

The birds raise their crests and may fly toward apparent intruders or competitors, perhaps jabbing them with bills, sometimes giving chase. Opponents try to snatch at each other’s heads. A bill injury may prove fatal.

Usually silent, herons deliver a “Frawnk” or rapid squawk to show alarm or aggression. A screaming “Awk” may arise from disturbed breeding colonies. A bird may squawk while feeding or landing, especially at a nest. While flying, birds may emit a “Gooo,” sounding like a calf’s bleat.

Once shot for meat and plumes and, as was fashionable in the late 1800s, decorative eggs, these herons’ populations were not as depleted as those of other shorebirds. While thriving, though, their populations appear to be decreasingly slightly.

Great Blue Herons do tolerate some human activities, but we must assure that they can breed undisturbed, as they flush more readily during breeding season. Erecting buffers like fences and ditches near their habitats may help.

The herons’ local predators, especially of their eggs and nestlings, include red-tailed and Harris’s hawks, raccoons, and fire ants. Birds may abandon colonies after predator attacks.

Leave a Reply