Nomenclature is a totally human activity; we are the only species — as far as we know — that feels the need to put a name to something. Psychologists acknowledge that there is great power in naming things — it indicates affection and triggers further bonding; naming cements psychological ownership.

As Texas Master Naturalists, knowing the name of different lizards, birds, plants, animals and even snakes and bugs allows us to put emotion into our interpretive talks. In the naming of things, our curiosity is assuaged, but more than that, knowing and classifying is a safety measure for the habitat. Once identified, a plant, critter or organism can be researched and studied and with knowledge, action can be taken against an apparent invasion, or conversely, something can be left to its own devices. Such was the case recently with an overabundance of hoppers.

A little backstory. Many of you know I keep a black light and moth sheet set up during the warm months of the year. An added benefit of the nightly set up is that more than just moths visit the sheet.

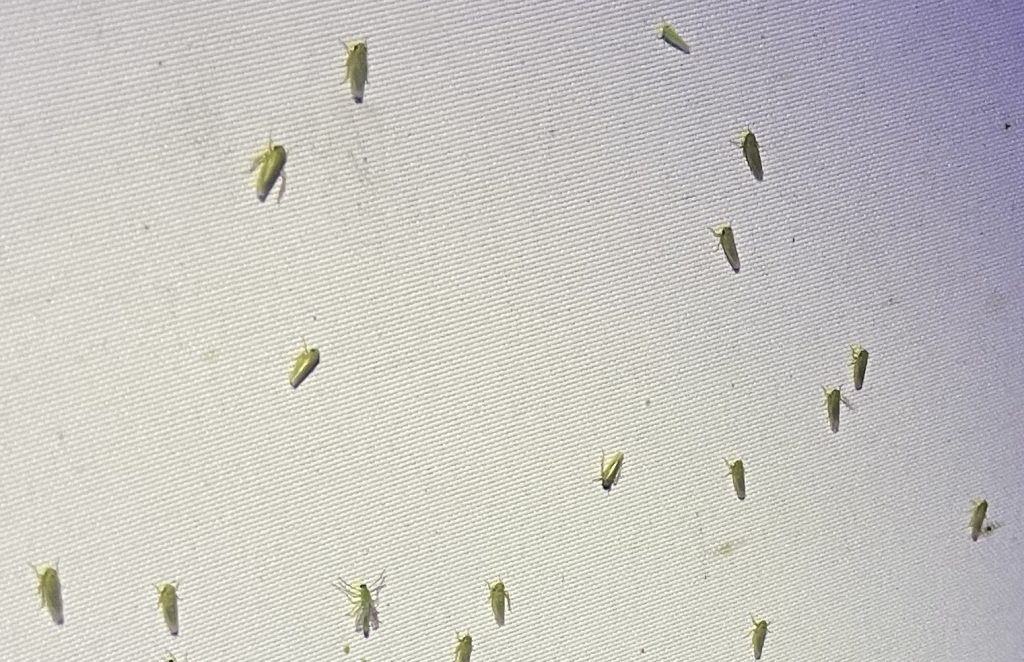

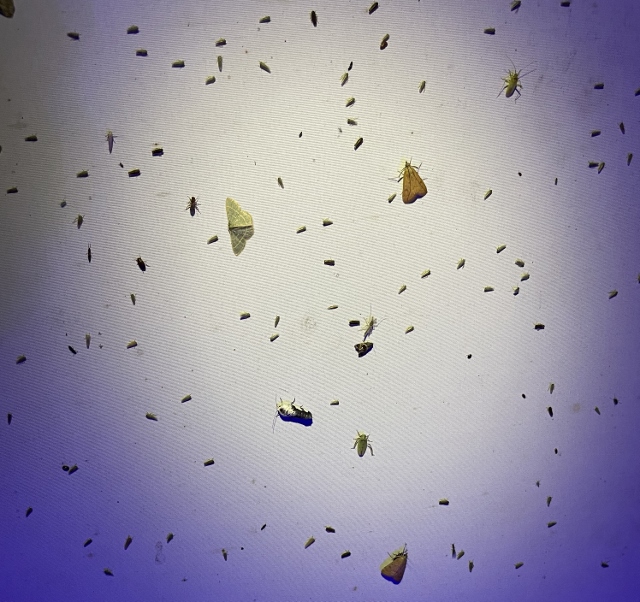

Mostly only one or two moths of a species show up at a time. Not so with bugs; they tend to congregate in groups — sometimes in hordes. But when seemingly legions of the same species cover the moth sheet, it’s time to take note — like the hoppers.

There are a lot of hopper bugs: Leafhoppers, planthoppers, treehoppers, froghoppers (spittlebugs) and, surprisingly, cicadas.

On two separate nights, hoppers came in droves to the moth sheet. The visitors at the first event were identified via www.iNaturlist.org as Citrus flatid planthoppers. A couple of nights later, potato leafhoppers had taken over the face of the moth sheet nearly to the exclusion of anything else.

Citrus flatid planthopper, Metcalfa pruinosa, fortunately, cause negligible damage; they are not a pest to worry about in your garden, according to www.tamu.edu. This species of insects are tiny: seven thirty-seconds to five sixteenth of an inch, in a compact, tent-shaped body. They are native to North America and found throughout southern Europe and in South Korea. Their color varies from whitish to light green.

Mouthparts are adapted for piercing and sucking. When they feed on sap, they eject excess sugar in the form of honeydew. This attracts bees, which convert it to honey.

The citrus flatid planthoppers can show up on various trees, orchard and citrus trees, grape and other vines, shrubs, herbs, field crops and ornamental plants. Host plants include willows, elms, black locust; crop plants include grape, citrus, peach, blackberry and raspberry. The adult lays eggs inside the stems of host plants; nymphs hatch in March and April and develop to adult by June. According to www.tamu.edu, a strong stream of water will knock these critters off plants, if there are too many for your liking.

There are more than 12,000 species of Planthoppers; they are in the bug order Hemiptera and superfamily Gulgoroidea. They vary in color, markings, geographic location and plant preference. Some species are attracted to lights at night. En masse, planthoppers can destroy plants; they also transmit pathogenic microorganisms that cause plant diseases.

Even though there may seem to be great numbers in my yard, I’m not compelled to take action. An environmental benefit is that planthoppers, and other tiny insects, play a role in feeding the young life stages of praying mantises, ambush and assassin bugs, spiders, Ladybugs, lacewings and other insect predators — all of which are generally found on or near the moth sheet. Planthoppers, as prey, convey nutrients created by plants up the food chain into larger insects that can be eaten by birds, reptiles and other larger animals.

~ ~ ~

The second invasion of hoppers, identified as potato leafhoppers, Empoasca fabae, are tiny, pale green bugs whose range is from North America, Mexico and Central America. Their host plants include about 200 cultivated and wild plant species, particularly legumes, according to www.bugguide.net. They are a pest of fruits and vegetables, alfalfa and a major pest of potatoes.

Leafhoppers, like planthoppers, are in the bug order Hemiptera. Their superfamily is Membracoidea (Cicadelloidea). There are estimated to be around 20,000 different leafhopper species; they can be found on all continents in nearly every habitat that supports vascular plant life, like deserts, grasslands, wetlands and forests. Vascular plants are those that circulate gases, water, minerals and nutrients through their tissues.

Leafhoppers are usually found feeding on the above-ground stems or leaves of plants. They pierce plant tissue and suck plant sap; they do not eat the plant leaves and stems. Adults are one eighth to one quarter inch long in shades of yellow, green and brown. Some are solid colored and some mottled. Leafhoppers have one or more rows of small spines on the hind tibiae (shin-like segments). Their bodies tend to be parallel-sided or taper toward the rear.

Leafhoppers are distantly related to planthoppers, froghoppers (spittlebugs), cicadas, scale insects, true bugs, whiteflies, psyllida and aphids.

Like their cicada cousins, leafhoppers sing using an organ called tymbals, which are located at the base of the abdomen. Unlike cicadas, they do not sing loudly enough for us to hear them, but they do hear and find each other, according to plantcaretoday.com.

Leafhoppers usually do not cause severe damage that would seriously harm mature plants in a garden. The best defense is to cultivate a diverse population of beneficial insects and natural predators, like parasitic wasps, assassin bugs, damsel bugs* (not damselflies but a beneficial bug in the Hemiptera order that feeds on field crop pests), tachinid flies, Ladybugs, robber flies, green lacewings, spiders, minute pirate bugs, lizards, wasps and birds — all species that make up a healthy habitat.

Hoppers have a strong jump which precedes the engaging of their wings. “The hopper families include some of the most powerful jumpers in the insect world, reaching acceleration forces of 50-Gs and more during take-off,” according to an article by Mike Merchant at this link:

https://citybugs.tamu.edu/2020/07/24/jumping-champs/. The article includes a link to a “fantastic new video” from North Carolina State Entomologist Dr. Adrian Smith that shows off the jumping prowess of the four families of hoppers.

Large infestations of any insect and invasive insects can produce devastating results to agricultural crops, gardens and native habitats. Local county Texas A&M AgriLife Extension agents can answer questions and provide information about local problems. A list of contact numbers for county agents is at this link: https://agrilifepeople.tamu.edu/contact-lists/public/units/p-counties